Stephen Roskill: Scholar-Archivist

Visitors to the Churchill Archives Centre may recognise the likeness between this photograph and the portrait which smiles down on researchers from behind the enquiries desk.

Photograph of Stephen Roskill from the Fellows’ Album, c. 1961, Churchill College Archives CCPH/1/6

When it was noticed in 1977 that no existing portrait of this particular person graced the walls of the main college building, a drawing on paper was commissioned by the Churchill College Fellows to hang permanently in the reading rooms. It was a fitting tribute to a man who had played a key role in the early development of the Archives Centre, bringing many important collections of military and naval papers to Cambridge.

Stephen Roskill (1903-1982) had a distinguished career as a naval officer and strategist before taking early retirement, partly on account of his increasing deafness caused by exposure to gun detonations (a particular specialism; Roskill had also been chief British observer at the Bikini Atoll atomic bomb tests in 1946). He would devote the rest of his life to historical research and writing, publishing the Cabinet Office’s official naval history of the Second World War (1954-1961); works on naval policy in the inter-war period; and several historical biographies, including a three-volume life of Maurice Hankey, first Cabinet Secretary (1970-1974).

The two World Wars set in motion a vast amount of archival collecting, both of public records and the private papers of public individuals who had served during the conflicts. In Britain, one of the first manuals for archivists and keepers of public records was published in 1922 as part of a Carnegie Endowment investigation into the impact of the First World War. Churchill College began to accumulate the personal papers of leading military, political, and scientific figures in 1965, with the aim of building a major centre for research into what was called the ‘Churchill era’. Churchill’s post-1945 archive would arrive in 1969 as a bequest from Lady Spencer-Churchill, joined by his pre-1945 papers in 1974.

As a Senior Research Fellow and historian, Roskill worked tirelessly alongside Sir John (“Jock”) Colville and the Master, Sir John Cockcroft, to seek deposits and collections to complement the Churchill papers. His extensive network of senior naval, diplomatic, and military contacts; his growing reputation as a scholar; and his personal charm (in spite of his deafness and love of spending time among his books, Roskill was said to be a great conversationalist) helped secure many of the Archive Centre’s great wartime collections. Roskill’s exhaustively detailed catalogues (e.g. to the Dilke-Crawford-Roskill Papers) and opinionated annotations as to the likely historical ‘value’ of individual documents have become slightly legendary at the Archives Centre. One former Archives Assistant commented:

“I always knew when he was in because I could smell cigar smoke… On one occasion, when I knocked on the Captain’s door to remind him that [smoking was not permitted in the Archives], he simply removed his hearing aid and grinned at me”.

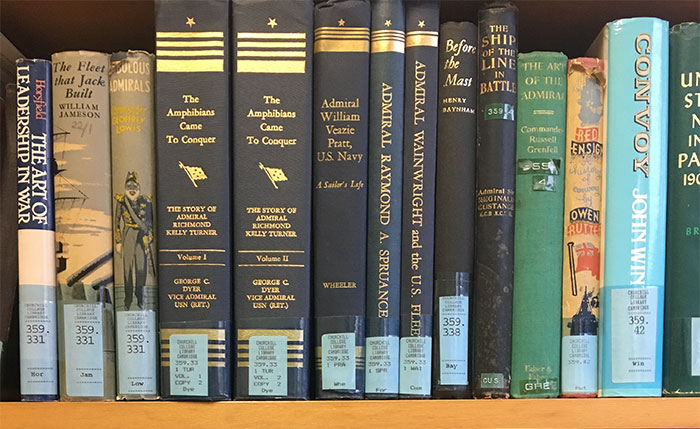

Roskill’s own papers, including his research notes and correspondence, were among the earliest accessions. Visitors to the reading rooms now work among his personal library (the books are freely available to borrow from the Archives Centre overnight on request).

Roskill had been awarded his research fellowship at the newly-founded College in 1961, ostensibly to pursue his work on a leadership manual for use in the training of élite naval officers by the Admiralty. The result, a short volume entitled The Art of Leadership (1964), is (by his own admission) the closest Roskill came to writing his autobiography, being deeply ‘mistrustful’ of memoirs as historical sources. Drawing on the insights of great leaders and travel writers, from Sir Walter Raleigh and Nelson to Churchill, Admiral Ramsay, and Freya Stark, the book combines guidance on naval discipline, administration, and speechifying with the historian’s own personal reflections on life at sea. It can also be read as a social commentary on the challenges posed by decolonisation, affluence, and the rise of youth culture during the ‘Churchill era’ – several themes which were to arise in later deposited collections. Steering impressionable naval recruits away from contemporary temptations such as alcohol, consumerism, and speculating on the stock market, Roskill argued, should be effected with good humour and the cultivation of ‘a sense of style’ on board ship (style, he says, ‘is inseparable from expertise’). Roskill anonymously donated the proceeds from this book to Churchill, where he also taught undergraduate historians and actively promoted the earliest College societies.

Roskill brought to his prodigious scholarly output ‘the same seamanlike attention to detail, order, and exactitude that he had shown in his naval service’ and a ‘prickly determination to stand firm for what he believed to be right, even in the face of pressure from the most eminent’, according to one contemporary. Indeed, Roskill was among the earliest and influential, though even-handed, critics of Churchill’s wartime leadership. He gave a first-hand account of Churchill’s interference in naval operations at the Admiralty, including the Norwegian campaign, during WWII in his official history, while his later work (1977) was critical of the politician’s approach to strategic planning for naval offensives throughout his career. Roskill was no mere polemicist, having a deep respect for traditions of scholarly research: his publisher reportedly said that ‘to get him to quote from a document instead of printing it in full was like drawing a tooth’.

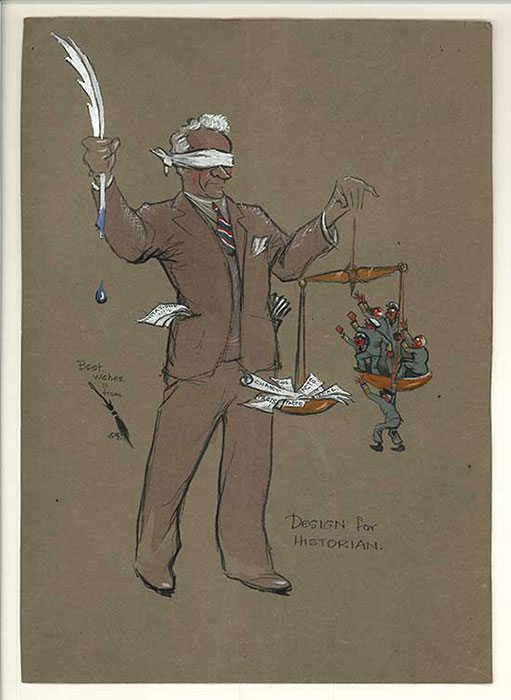

A cartoon by Roskill’s close naval contemporary, Captain Jack Broome, illustrates Roskill’s perennial dilemma in trying to balance his conflicting loyalties: an obligation to write the truth about the two World Wars as it arose in the archival record (represented here as a stack of ‘charts’, ‘facts’ and ‘figures’), counterbalancing the weight of opposition and lure of ‘invitations’ from the British establishment.

‘Design for Historian’, cartoon sent to Stephen Roskill by Sir Jack Broome, c. 1954, ROSK 14/2A.

Roskill died in 1982. Correlli Barnett, the first Keeper of the Archives Centre, proposed a unique and prestigious memorial: a biennial lecture to be delivered at Churchill College by a ‘person of world stature’, covering key themes in the Archives Centre’s collections: international security, foreign policy, war, public policy, and the history of science.

Catalogue to the Roskill Papers

— Heidi Egginton, Archives Assistant, January 2018