Churchill Archives Centre: The Story So Far...

The origins of the Churchill Archives Centre can be traced back almost to the beginnings of Churchill College. Founded in 1960 as the National and Commonwealth memorial to Sir Winston, the College was always intended to be “a bridge between the achievements of the past and the possibilities of the future”.

The aim of this venture is to make the College a major centre of historical research into what might be termed the Churchill Era, where scholars will be able to find a great mass of inter-related material gathered together under a single roof”.

Sir John Cockcroft, Master of Churchill, letter of 14 July 1967

The College began to collect papers in 1965, with some of Lord Attlee’s papers forming the first major accession. Three individuals played prominent and complementary roles in laying the foundations of the Archives Centre: Sir John (“Jock”) Colville, former private secretary to Sir Winston and a trustee of the College, who was influential in securing the papers of leading political figures, including many of Sir Winston’s Cabinet colleagues; Captain Stephen Roskill, celebrated naval historian and Senior Research Fellow, who was equally well connected, with links to many senior military figures; while the first Master, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Sir John Cockcroft, had rich contacts throughout the scientific community. Between them, these three established the collections policy that continues to this day, bringing together the private papers of the politicians, service-chiefs, diplomats, civil servants, scientists and technologists who have shaped the history of our recent past.

The Archives Centre was initially an adjunct to the College Library, but there was always the ambition to become something much bigger. The hope was that Sir Winston’s own papers would form the centrepiece of a new Churchill Archives Centre, and this dream came a step closer in 1969 when Lady Spencer-Churchill gifted her husband’s post-1945 papers to the College.

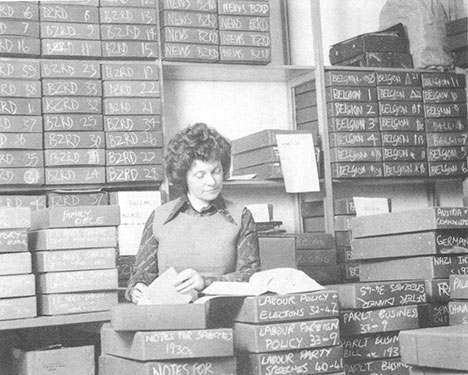

Part of the Churchill Papers.

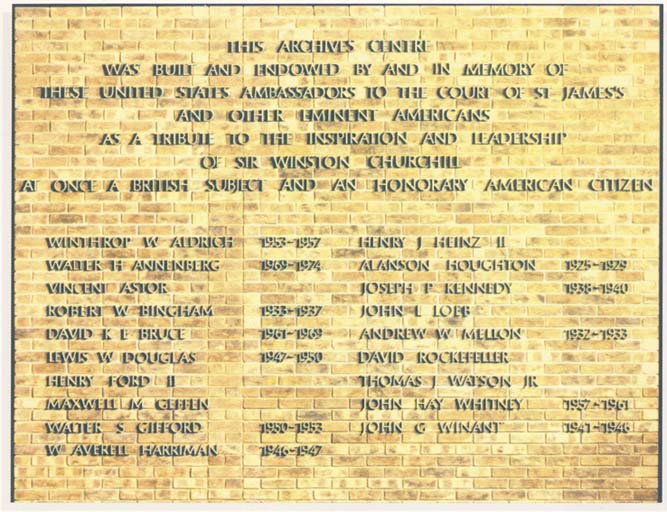

Plaque commemorating the American Ambassadors who contributed to the building of the Archives Centre.

Faced with a rapidly expanding collection, the College began to look seriously at the creation of a dedicated Archives Centre. The task fell on Dr Michael Hoskin, a Fellow of the College and prominent historian of astronomy, when he agreed to become Librarian:

“In 1969 I received a phone call from the Vice-Master of Churchill, telling me that the college expected to be the repository of the papers of Sir Winston Churchill, and inviting me to become Librarian with a view to constructing an Archives Centre.

“The challenge was intriguing. The Library, I found, was established and running, a service primarily to the undergraduates of the college. Behind the Library Office was a large interior room fitted out with motorised shelving, and here were kept the collections from the Churchill Era that had so far been assembled. On a top floor was a large room with little contact with the outside world, and there dwelt the Archivist. Soon he was to be joined by the Conservationist that I appointed, an uneasy coexistence as the noise made by the Conservationist frayed the nerves of the Archivist.”

A new building was clearly needed, and the primary task was to raise the necessary funds. As Dr Hoskin explains, it was Jock Colville who came up with a winning strategy:

“Many features of the college were gifts of allied governments, for the college was the National Memorial to Sir Winston, but curiously there was no American gift. Jock conceived of the idea of approaching all the US Ambassadors of the Churchill era, or their families, inviting them to contribute a share of the cost of an Archives Centre; and in this he was successful, though an endowment of the building and staff was still a matter for the future. With the cost of the bricks and mortar assured, the college agreed to go ahead.”

Dr Hoskin persuaded the College that the Archives Centre should be built at the heart of the campus. The design was then approved and commenced. The opening was performed by the United States Ambassador, Walter Annenberg, on 26 July 1973 in the presence of the Duke of Edinburgh and Lady Spencer-Churchill. As Hoskin recalls, “It was a memorable day, not least because Mr Annenberg on arrival at the college eluded his secret service guards and presented himself to me at the Archives Centre itself, when he should have been in the party welcoming the Duke’s helicopter.”

The Archives Centre now had the space to expand, and expand it did. Moreover, as the archive collections were now physically separate from the library, it made sense for them to be managed separately. The post of Keeper was formally separated from that of Librarian, and the first holder of the new office was the military and industrial historian Correlli Barnett. He took up his responsibilities on New Year’s Day 1977, little knowing that he would remain in office for the next eighteen years and lead a large and sustained expansion of staff, public services and collections. Further fund raising became a central task, but enabled the Centre to keep pace with new technology and standards, providing air conditioning for the conservation workshop, CCTV for the reading rooms, and the first photocopier and computers for the offices. To quote Correlli Barnett, “as is usual with fundraising, all this proved a long, hard slog. Yet without it the Centre would have remained stuck in the era of pencil-and-paper, the card-index, and the typewriter.”

Prince Hassan of Jordan giving the 2005 Roskill Lecture.

The pre-1945 Churchill Papers had arrived in 1974, although they remained in the ownership of a private family trust. Now Sir Winston was gradually surrounded by famous faces, some familiar, some new, as the Centre acquired the archives of Lord Duncan-Sandys, Lord Hailsham, Field Marshal Lord Slim, Lord Selwyn Lloyd, Admiral Lord Fisher, Sir John Colville, Lady Spencer-Churchill, Lord Brockway, Lord Noel-Baker, Lord Todd, Lord Soames, Sir Ove Arup, Sir Hermann Bondi, Neil Kinnock, and Rosalind Franklin among others [see our Full Guide to Collections].

The death of Captain Roskill in 1982 was a huge loss to the College and the Archives Centre, but it at least led to the establishment of a unique and prestigious memorial. Correlli Barnett explains:

“I proposed to the Archives Committee that an appropriate way of commemorating his unique contribution to naval history, to the Archives Centre, and to the College would be a ‘Stephen Roskill Memorial Lecture’, to be given in the Wolfson lecture hall every other year. I was determined that this should not be just another run-of-the-mill Cambridge lecture but a major event, and that therefore the inaugural lecturer must be a person of world stature. In 1984 the first Roskill Memorial Lecture was delivered to a capacity audience by Lord Carrington, Secretary-General of NATO. The Archives Centre took main responsibility for all the lecture arrangements and hospitality, as it still does today.”

Since its inception, the Roskill Lecture has been delivered every two years. The lecturers since Lord Carrington are Professor Sir Michael Howard, Field Marshal Lord Carver, Sir Brian Urquhart, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Julian Oswald, Mr Mark Tully, Professor Paul Kennedy, Sir Colin McColl, Professor Peter Hennessy, Ms Bridget Kendall and Prince Hassan of Jordan.

A comparable development was the establishment of the Archives Fellow Commonership (now a By-Fellowship) designed to allow a scholar from outside Cambridge to reside in College for a term or longer in order to pursue their research. This scheme was also instigated by Correlli Barnett, who recalls the first Archives Fellow-Commoner, the distinguished American naval historian Jon Sumida:

“Since he also played the trumpet in the College Orchestra, Jon Sumida brilliantly inaugurated what remains today an important institution within the life of the College and the Archives Centre.”

In March 1994 the Archives Centre staged its first academic conference on Sir Winston’s statesmanship in the College’s new conferences Møller Centre. The event drew speakers from around the globe and resulted in a book, thereby firmly establishing the reputation of the archives as a centre for Churchill scholarship.

Yet the long-term future of the Churchill Papers had still not been secured, and complex negotiations were taking place behind the scenes. Correlli Barnett again,

“Along with fund-raising, the major anxiety of my Keepership lay in the uncertain future of the Chartwell Papers (Sir Winston Churchill’s papers from childhood to 1945). From 1988 onwards the Archives Centre and the College found themselves caught up in complex negotiations between a Churchill family trust and the Government over the possible purchase of the Papers by the State.”

The Centre invited inspection by the Cabinet Secretary and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, and was validated as “in every respect a worthy permanent repository” for the Chartwell Papers once a settlement had been reached.

Dr Piers Brendon took over as Keeper in time for the final stage of the negotiations. The papers were bought for the Nation from the Chartwell Trust for £12.5 million, with a further £1.75 million coming to the Archives Centre for cataloguing, conservation and endowment. £13.25 million came from the newly established Heritage Lottery Fund. Dr Brendon and the Archives Centre were suddenly front page news:

“…its announcement caused a furore. But, as we pointed out to the enormous number of press enquiries at the time, there is no doubt that the grant was well spent. All the Churchill Papers (including the post-1945 Papers, which Clementine Churchill had given to the College and which it contributed as “matching funding”) remained together in the building that was designed to hold them. They were vested in an independent charitable trust, the Sir Winston Churchill Archive Trust, whose first chairman was Andreas Whittam Smith. And in purely financial terms, as subsequent sales of holograph Churchill letters showed, the nation got a bargain.”

The aftermath of the lottery purchase saw the staff of the Archives Centre double in size in order to undertake an ambitious five-year programme to conserve, catalogue and display the Churchill Papers. Software was purchased and modified for this formidable task, summarised here by Dr Brendon:

“A huge effort was made to modify it to our needs. Five years’ work by five archivists, cataloguing perhaps a million individual pieces of paper in the Churchill archive, produced the finished catalogue in September 2000. “

The New Wing, 2002.

Major Churchill exhibitions were staged at the Public Record Office in London (now the National Archives), the John Rylands Library in Manchester, and the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh. In addition, a rolling display of documents was set up at the Cabinet War Rooms beneath Whitehall. Yet, as Dr Brendon points out:

“These major projects did not prevent the prosecution of others, such as the Diplomatic Oral History Programme, which collects the diplomatic “history behind the history”. Nor did it interfere with the acquisition of important new collections of papers, including those of Sir Frank Whittle, R.V. Jones, Sir Frank Roberts and Enoch Powell.”

Most important of all was the acquisition of the papers of Baroness Thatcher of Kesteven, first female Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and longest serving Prime Minister of the twentieth century. The papers arrived in 1997, though discussions had begun years before. Correlli Barnett remembers the initial contact:

“In 1993 I was invited by a mutual friend of myself and the Thatchers, Mr Ron Gerard, to talk informally about the life of a writer to a private luncheon he was giving at the Carlton Club. There I was introduced to Denis Thatcher, who expressed interest in the fact that I was Keeper of the Churchill Archives Centre. Only the previous evening, he told me, he and Margaret had been arguing as to whether Churchill College was in Oxford or Cambridge. I was able to assure him that Churchill was indeed a Cambridge College, whereupon he accepted my open invitation to himself and Lady Thatcher to visit the Archives Centre.”

In due course they both came, followed by the papers and the appointment of a dedicated archivist to catalogue them. They are now the property of a charitable trust established and chaired by Lady Thatcher herself.

The arrival of the Thatcher collection, coming fast upon the acquisition of other sizeable collections, took the existing Archives Centre strongroom to capacity and necessitated the advent of a new building project, the latest chapter in a dynamic history. Sir Denis Thatcher visited the College on 19 July 2001 and formally cut the turf for the new wing of the Churchill Archives Centre. Construction commenced in August and finished in June 2002.

Designed by Cambridge architects, Thurlow, Curtis and Carnell, the building comprises four storeys of secure archival storage. It has been constructed to an extremely high specification, designed to meet the relevant British Standard and to accord with the latest guidelines from the Historical Manuscripts Commission.

The new wing will provide the permanent home for the Thatcher papers. Yet it will also be much more than this, trebling the capacity of the existing Archives Centre, and allowing it to continue to collect, preserve, conserve and make available the raw material of history. The Archives Centre also sought to use this opportunity to upgrade its existing facilities, and improvements include a passenger lift linking the Jock Colville Hall to the Roskill Library and reading rooms.

Since its inception, the Churchill Archives Centre has grown to become one of this country’s leading repositories for the preservation and study of modern private papers in the fields of politics, public life, diplomatic and military service, science and engineering. Sir Winston Churchill was interested in all of these areas, and it seems appropriate that, within the walls of his National memorial, he will continue to gather around him many of the individuals he helped to inspire. Recent acquisitions have included the papers of Lord Young of Dartington, and a large additional deposit of the records of the late Lord Hailsham of St Marylebone.

Churchill College and Archives Centre are grateful to Baroness Thatcher and the donors to the new wing for helping to make the expansion of the Churchill Archives Centre a reality. The challenge now is to build upon these solid foundations and to ensure that the material within the archive fulfils its potential, helping to shape and inform education, research and debate for generations to come.

Positive steps have already been taken in this direction. The catalogue to the Churchill Papers went on-line at the end of 2001, and other collections are already following suit. The Centre has also been developing an educational website, The Churchill Era, based on its holdings, and continues to build partnerships with related archives, libraries and museums throughout the United Kingdom and beyond. Trans-Atlantic links remain of particular importance, and the Archives Centre continues to benefit from a tradition of generous American support for its activities. Such links should work both ways, and the Archives Centre is exploring ways of strengthening its relationship with related libraries and institutions in the United States.

This text has been narrated by the Keepers and Director of the Archives Centre. Yet all of us are in agreement that the Centre owes its success to the hard work and dedication of its staff. There are too many to name individually, although the first conservator, Mr Victor Brown, deserves a special mention for having worked on the collections for almost thirty years.

Much has been done, and much remains to be done. To conclude by quoting Churchill’s first speech as Prime Minister in May 1940, Let us go forward together.

Allen Packwood

Director

June 2002

Chapter Two: A Period of Expanding Horizons, 2002-2012

The construction and opening of the New Wing confirmed that the Churchill Archives Centre would go on collecting. The main challenge now switched from securing our facilities to providing access to our collections. The College took the bold decision to support the Archives Centre in a major campaign to raise its profile and secure the endowment funds required to staff the preservation and cataloguing of its holdings. An American style development model was adopted, and the Centre was lucky enough to recruit Douglas N Daft, former Chairman and CEO of the Coca Cola Company, and then Scott B Kapnick, formerly Co-CEO at Goldman Sachs, to co-chair its Campaign Board. As of 2013, both men remain Patrons of the Churchill Archives Centre, and Doug now serves as the Chair of the revived Patrons Board. The Capital Campaign was launched in 2004 and ran till 2007, raising over £2.5M for the Centre. The names of the donors are recorded with gratitude on the Archives Centre website and on the glass wall of the Roskill Library reading room.

If the Centre was to raise money, then it also needed to raise its profile, to demonstrate that its collections were of international importance, and to show that it was serious about widening access. The Capital Campaign was launched against the backdrop of the major exhibition “Churchill and the Great Republic”, a collaboration between the Churchill Archives Centre and the Library of Congress, which was staged at the Library on Capitol Hill in the heart of Washington DC from February to June 2004. This is how I described the opening in the Churchill Review for 2004:

“I took up my second row seat in the ornate marbled surroundings of the Great Hall of the Jefferson Building in the Library of Congress, and waited. There was a buzz of expectation from the hundred or so specially invited guests, but little to do except watch the media cameras jostling for position, and return the stares of the special service agents. After about an hour there was an announcement, “Ladies and Gentlemen, the President of the United States”. George W. Bush strode purposefully to the Presidential lectern and delivered a foreign policy statement with the Churchill exhibition as a backdrop. The speech was broadcast with the by-line “President opens Churchill exhibit”, and I watched as a display that had been three years in the planning went primetime. “

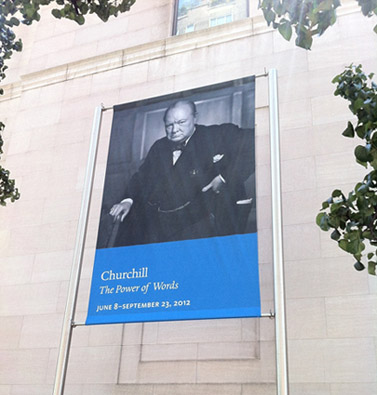

This proved the first in a number of high profile exhibition and outreach initiatives staged by the Churchill Archives Centre. There were two highly successful partnerships with the Howard H Baker Center for Public Policy, at the University of Tennessee. The first was a conference on “The Legacy of Churchill’s Atlantic Alliance”, held in Knoxville in 2006, just after the sixtieth anniversary of Churchill’s famous ‘Iron Curtain’ speech, and featuring Senator Baker and Henry Kissinger along side Lord Powell and Churchill grandson and namesake, Winston Churchill. The second was a two day international conference at Churchill College in November 2009 on “The Cold War and its Legacy”. This brought representatives from Russia, the United States, the UK, China, Germany, India, Japan, and Romania together to discuss all aspects of the Cold War; from origins to conclusion, and from intelligence to science and technology. Thereafter, the Archives Centre staged a conference in Singapore (2010), loaned materials to a Churchill exhibition in Madrid (2011), displayed key pages from Churchill’s 1941 speech to the Canadian legislature within the Parliament building in Ottawa (2012), and curated a major exhibition entitled “Churchill: The Power of Words” at the Morgan Library in New York (2012). The latter received excellent media coverage in the United States, including a two page review in the New York Times, and was seen by an estimated fifty thousand plus visitors.

Those may have been the main events, but they were only the tip of the iceberg. In between times, the Centre staged Roskill Lectures, several Thatcher era witness seminars, hosted hundreds of group and VIP visits, and enjoyed working on programmes with Elderhostel, Lombard Street Research, and CRASSH (Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Cambridge). A small joint exhibition at the Palace of Westminster with the History of Parliament Trust in 2006 was opened by the then Prime Minister, Tony Blair.

If one of the main aims of this outreach was to increase research use of the collections, then all the indications are that Centre was successful. Totalling up the figures from the annual reports for this ten year period, 2002 -2012, we can claim to have issued a staggering 77,948 documents to 4,470 researchers making 13,896 daily visits. This does not include visiting groups or enquiries dealt with remotely, by post, telephone or increasingly by email.

Morgan Library exhibition, New York 2012.

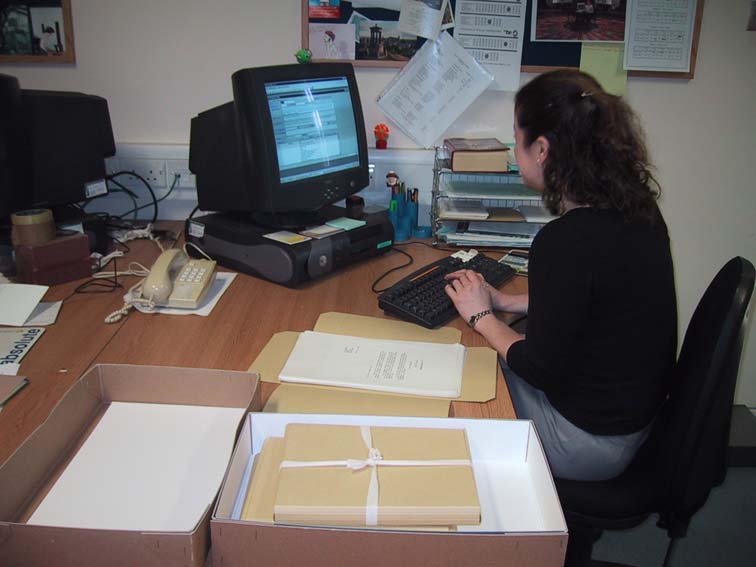

John Major’s papers.

There can be little doubt that one of the reasons for the increased usage was the provision of better information about our collections. Not only was the catalogue of the Churchill Papers made available on-line, but collection level descriptions, catalogues and lists for all the collections were standardised, enhanced and made accessible via the University of Cambridge’s ArchiveSearch web server. Linked to the Archives Centre’s own website, ArchiveSearch effectively provided a portal that made the content of the Centre visible to users around the globe. On-line information about collections also fed into the digitisation of the archives themselves. By the end of 2012 the Churchill Archives Centre had scanned Lady Thatcher’s personal papers up to 1990, some 900,000 pages in total, and had also helped Bloomsbury Academic launch The Churchill Archive Online, the comprehensive electronic publication of the Churchill Papers collection.

New collections continued to come in throughout this period. Between 2002 and 2012 the Churchill Archives Centre accessioned the papers of one Prime Minister (Sir John Major), several prominent Cabinet Ministers (Lord Carrington, Robin Cook, Lord Howell, Sir John Nott, Lord Rawlinson, Lord Ridley, Lord Wakeham, Lord Whitelaw), some prominent figures from public and political life (Tam Dalyell, Lord Donoughue, Sir Bernard Ingham, Peter Jay, Lord King-Hall, Sir Alan Walters), a sculptor (Oscar Nemon), two high profile members of the Churchill family (Randolph Churchill, Winston Churchill), and five Nobel Prize winning scientists (Max Born, Sir Robert Edwards, César Milstein, Max Perutz and Sir Joseph Rotblat), including Rotblat’s award for peace. The strength of the archive as a whole was recognised with the award of Designated Status by the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council (MLA) in 2005. The press release confirmed that:

“The Designation Scheme aims to identify and celebrate the best museum, library and archive collections in England; those that are deemed to be of outstanding national and international importance. The Scheme recognises that organisations with Designated collections care for a significant part of England’s cultural heritage. It was launched in 1997 for museums only, with two further rounds in 1998 and 1999, and extended to libraries and archives in 2005”.

Much work was also done to make collections available, and the large archives of Leo and Lord (Julian) Amery, Max Born, Lord Hailsham, Peter Jay, Lord (Neil) Kinnock, Reginald McKenna, Oscar Nemon, Enoch Powell, Sir Edward Spears, and Lord (Michael) Young were all catalogued. This represents an extraordinary amount of work by the conservator, archivists and archives assistants on the Archives Centre team.

2013 began with the announcement that the papers of Gordon Brown would be deposited at the Archives Centre. And so the next chapter begins. It seems we are set to become a truly twenty-first century archive, and are preparing to face the challenges of electronic records and internet access.

Allen Packwood

15 February 2013