The opening of a new decade often inspires a look forward to the future, and sometimes a nostalgic look back too. As 1970 opened, the greatest decade in the history of mankind was over (to misquote a line in a later film). It was an obvious moment to take stock of the nation’s mood and wellbeing.

Mark Abrams, c. 1956 (ABMS 8/1/22). Reproduced with permission of Dominic Abrams.

Churchill Archives Centre holds the extensive records of Mark Abrams, a long-standing specialist in using statistical surveys for market research on popular attitudes. The collection was beautifully catalogued by Dr Heidi Egginton in 2017 and is now fully open to researchers. See Heidi’s blog on the collection.

From 1965, Abrams had been involved with The Committee on the Next Thirty Years, a sub-committee of the Social Science Research Council (SSRC). Abrams, working with the sociologist Michael Young, set out to investigate the deployment of the social sciences to help forecasting the future and inform policy-making. Abrams and Young, concluding “Freedom can only be maximised if people are prepared to look far into the future with a sophistication much greater than they have usually shown so far”’ [ABMS 4/5, 1966].

As the new decade came, Abrams was involved in a sample survey in the Netherlands in early 1970 to gauge public opinion about contemporary Dutch society and the likelihood and desirability of certain social changes there over the following ten years to 1980.

In a wonderful and far-reaching interview, conducted in 1984 with his grandson Dominic, Abrams recalled that he had been asked:

to do surveys among the Dutch people as to what they thought about the future, what they thought was a desirable future, as distinct from what they thought would be the future. And compared the Dutch public views with the views of the Dutch élite on that. And, crudely, what happened was that what the Dutch public thought was going to happen materially was going to be fine, but what was going to happen morally was going to be pretty awful, drug addicts all over the place, kids not working, not being interested in work, increasing the crime. But they’d all be better off, they’d all have a lot more money. What the élites thought was that, morally, every Western country would be finer, freer. They’d have wider outlooks, there’d be more humanitarianism. But unfortunately, they wouldn’t be economically so well off. This was a very interesting contrast in between the two.” [ABMS 7/1/2].

Abrams being interviewed, 1984. Ref: ABMS 8/1/28

Research phase of future perspectives

In April 1970, Research Services Ltd (Abrams’ company) was commissioned by the SSRC to conduct a British study of perceptions of the future. (The report to be known as ‘Future Perspectives’ was ultimately finished in November). Preparatory research work started in April 1970, while the rest of the nation was pre-occupied with the fate of the Apollo 13 mission and the announcement by Paul McCartney that he was leaving The Beatles.

Abrams initially assembled 33 interviewees in four discussion groups, two held in London and two in the north of England. These groups were balanced by gender and class, with a numerical bias to younger discussants. The comments from the discussion groups helped to finalise the subjects chosen and the design of the questionnaire to be used by Abrams’ team of interviewers.

After the research phase, it was decided that looking forward 30 years would lack focus. Instead, the questionnaire would be based on a shorter period of 15 years (‘a date close to 1984’ as the introduction to the final report notes, hinting at the Orwellian resonance of that year [ABMS 3/202]). Reflecting Abrams’ Dutch experiences, the samples were designed to cover both ‘younger section of the public’ (defined after the research phase as ages between 16 and 45 years old) and ‘the elite’ (those in a position of power and influence in Britain).

The only obstacle in rolling out the survey interviews was the 1970 General Election, called, rather unexpectedly, for June 18 that year. However, the survey, unlike the 1970 football world cup, could wait for the election result. It has been argued that England’s defeat in the world cup might have cost Harold Wilson an election victory but it’s less clear if this affected the survey data collected by Abrams on the national mood.

The interviews

The public sample was eventually interviewed between 1st and 10th July 1970. The sample of younger members of the general public group included 586 people aged between 16 and 44. The sample was based around 25 representative local government areas based “south of the Caledonian Canal” (running roughly from Fort William up to Inverness).

The elite members questioned by Abrams’ team were, by definition, a smaller sample of 50 people. The interviews with the elite were conducted with a balanced selection of those in high positions in industry, finance, local government, the civil service and the trade unions. This group tended to be older and all but one were male. The elite interviews were conducted between 10th July and 30th August. Because of the less structured approach for the interviews of the elite group, they were conducted by executives from Research Services. (The general public group had been interviewed by more junior field workers.)

The interviews for the general public sample were concerned with obtaining an assessment of how people rated future changes for the specific items raised with them. Where possible, the questions were designed to feel open-ended and not constrained by the pre-set nature of the questionnaire’s design. In practice, it was recognised that the interviewees tended to restrict themselves to a few subject matters, obviously the most salient in their minds.

By contrast, it was anticipated that the elite group would be more articulate and would have at least some professional interest in future developments. The elite questionnaire was designed to allow more open questions and comment.

The conclusions

In November 1970, the report was ready. Exactly fifty years later, it makes fascinating reading.

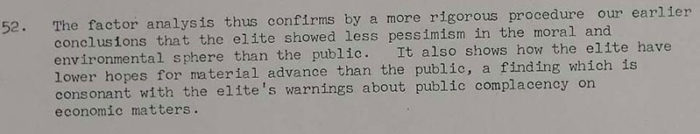

The headline summary of the report was that both the general and elite samples were inclined to view life over the next 15 years with a sense of optimism. At a deeper level in the general sample, though, optimism prevailed for key issues such as future material prosperity and technological advance, but there was considerably more pessimism in the fields of moral development, the quality of life and the state of the public environment.

The general sample’s combination of “technological optimism” and “social pessimism” was not wholly shared by the elite group. Rather, the elite sample was much more concerned about the intractable economic problems of the era and much less worried about the social issues of the day. (Abrams’ team put the change in emphasis down to class, rather than age, differences.)

Reference: ABMS 3/202

The report includes a fascinating tabulation of issues raised spontaneously in the interviews by the groups. Many of the concerns raised were similar but a much large number of the elite group mentioned future entry to the European Common Market as a favourable and natural development, as well bringing up concerns over labour and management relations.

At the end of the elite interviews, the sample was asked where they supposed the general public answers would differ from their own. Their remarks mostly frequently concerned two topics, the Common Market (again) and future living standards and material prosperity. Many of the elite group considered that the general public could only think of the short-term unfavourable aspects of joining the EEC (specifically, higher food prices) and not the long-term positive effects. Abrams and his team agreed in their report that this perception was accurately supported by the public survey data.

On the issue of living standards, Abrams’ report also noted that

the elite maintained over and over again that the public failed to appreciate that the material prosperity which they hoped for or expected could only be achieved by greater working effort or industrial efficiency and that the public could not see that the achievements of these aims was dependent on their actions.” [ABMS 3/202]

Futurology

Inevitably, some but not all of the predictions of both groups came to pass. Some trends took considerably longer than 15 years to come to fruition. Others remain unfulfilled today.

The elite sample were much more optimistic than the general public group in a range of categories including that families would have cars and telephones, that men and women would take equal shares of housework and looking after children and that ordinary people would have their complaints against the state satisfied.

By contrast, the public sample anticipated that there would be twice as many official forms, children of 15 would be less under parental control, most main roads would be choked with cars, women would be equal with men in education, job opportunity and pay, and that most people would live in flats.

Intriguingly, over half of the public group predicted that ‘some major national decision will be taken by a poll’, anticipating the 1975 referendum on membership of the EEC by some five years.

Reference: ABMS 3/202

Collecting archives of the social sciences

The Abrams papers are now part of a significant body of material held at Churchill Archives Centre of those involved in social science research in the latter half of the twentieth-century. The most significant are those grouped around Michael Young and his work at the Institute for Community Studies, including the diaries and papers of the sociologists Phyllis and Peter Willmott. The Centre also holds the papers of Paul Barker, editor of the hugely influential “New Society”, and of James Cornford, a prominent social reformer.

These materials already provide a very rich resource for the study of the social history of post-war Britain. The Archives Centre is delighted that they have been showcased in David Kynaston’s detailed post- war social histories, and also in specific recent studies by Jon Lawrence (“Me, me, me: the search for community in post-war England”, 2019), Lise Butler (“Michael Young, Social Science, and the British left. 1945-1970”, 2020) and Peter Mandler (“The crisis of the meritocracy: Britain’s transition to mass education since the Second World War”, 2020).

Collection development in the area of the social sciences is currently one of the Centre’s key collecting priorities.

Andrew Riley, November 2020

Subscribe to Churchill Archives Centre News

Enter your email address:

Subscribe to the Churchill Archives News RSS feed: