I was so fortunate to begin my relationship with the Churchill Archives Centre as a student in 2013-2014, when I was at Christ’s College in the MPhil in Modern European History program working on a dissertation on First World War postal censorship under the expert supervision of Professor David Reynolds. Little did I know that after graduating, I would be back for more—and much sooner than I could have expected.

After an idyllic year in Cambridge, I returned to the US to take a job as a financial analyst in New York City, but by sheer coincidence, in the lobby of my office was a bookstore—Chartwell Booksellers—named for Winston Churchill’s beloved country home. On coffee breaks, I found myself wandering into the Churchill-themed bookstore, admiring their many first editions of Churchill’s own works and reminiscing with the store’s owner about my last year of research at Cambridge and the Churchill Archive Centre. He must have found my interest amusing and at least somewhat endearing, because a few months later, he offered to introduce me to the International Churchill Society. They were having a dinner at the Waldorf Hotel, just across the street from my office, in honor of Madeleine Albright. If I was interested, I was welcome to join them.

Life’s twists and turns occur when you least expect them. At that dinner, I met the International Churchill Society (ICS) and members of the Churchill family, an encounter that would shape the next few years of my life. Shortly after that dinner, the Churchill family was opening the papers of Winston Churchill’s middle daughter Sarah, and the ICS asked if I was interested in writing an article about her collection for their magazine, Finest Hour. I knew little about Sarah, other than that she had been an actress and dancer who had starred in a movie with Fred Astaire, but even with little knowledge, I didn’t hesitate to say yes. Writing this article meant a chance to return to Cambridge and to the Churchill Archives Centre. It also felt as if fate was at play, because every summer since I was a little girl, I had walked past a picture of Sarah Churchill on her wedding day. Sarah had eloped to the Cloister at Sea Island, GA in 1949 with her second husband, Antony Beauchamp, where a striking photograph of Sarah in her wedding dress has hung on the wall ever since. My family has been visiting The Cloister since I was a baby, and I had always admired this photograph and wondered about Sarah’s life. Here was my chance to learn more.

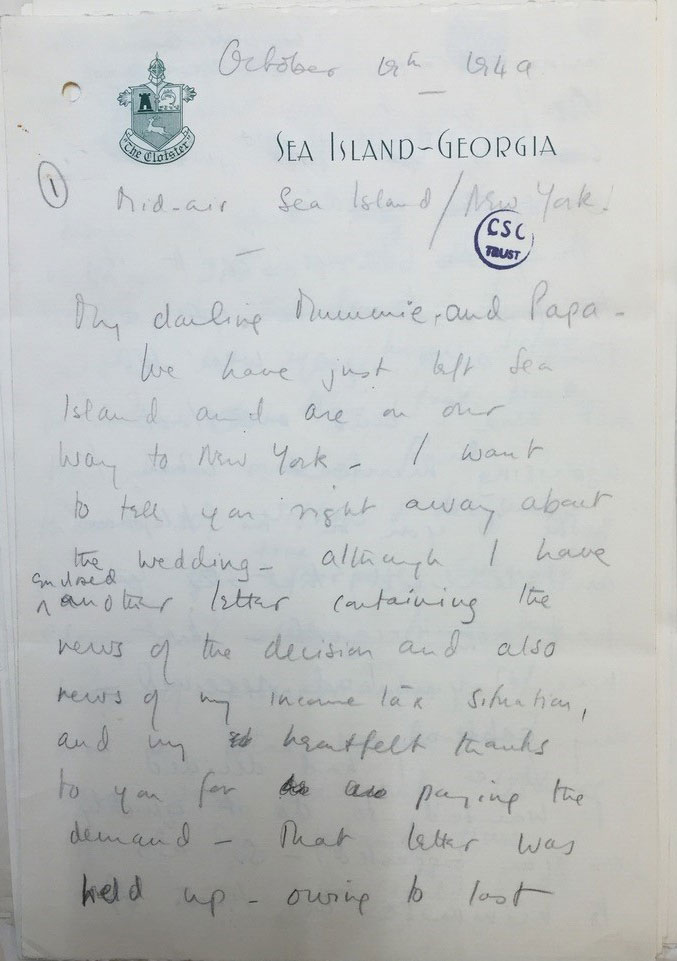

Letter from Sarah to Clementine about her wedding, October 19, 1949. Reference: Sarah Churchill Papers, SCHL 1/1/12

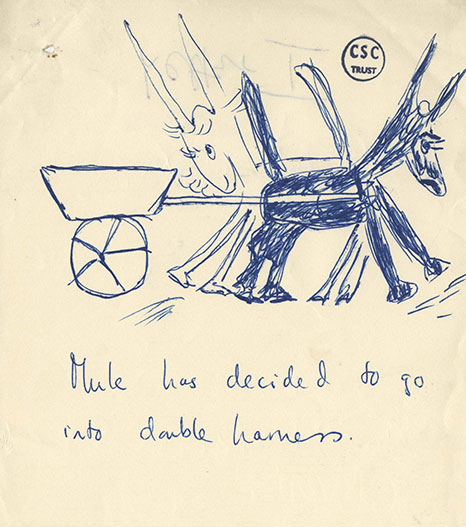

That winter, I made the trip back to Cambridge. Allen Packwood and his team are unparalleled experts in their field, and it was such a pleasure to work with them once again. My time in Cambridge was short, so over the course of three frantic days, they brought out folder after folder of Sarah’s papers in quick succession while I photographed her collection. As a Cambridge student, I had the luxury of time to pore over papers as I read them, but for this project, I had to photograph quickly and analyze later. Still, Sarah’s writing pulled me in, and I found myself pausing to pore over certain letters, many of which included charming sketches. The life of a young woman coming of age in the interwar and wartime period unfolded before me, Sarah’s writing as lyrically vivid as that of her father at his best.

Sarah’s sketch to Clementine announcing she had eloped with Antony Beauchamp, October 1949 (her pet family name was “the Mule”). Reference: Sarah Churchill Papers, SCHL 1/1/12

What struck me in particular were Sarah’s letters to her mother written during the war. When war broke out, Sarah left the stage in order to become a Section Officer in the Aerial Reconnaissance Intelligence Unit of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force at RAF Duxford. Sarah excelled at her job, and soon a thrilling new opportunity presented itself: the chance to accompany her father, the Prime Minister, as his aide-de-camp at the Tehran Conference with Roosevelt and Stalin in 1943. At the conference, two other fathers—President Roosevelt and the American Ambassador to the Soviet Union, W. Averell Harriman—took notice of how valuable she was to the Prime Minister. And when it came time for the Yalta Conference in February 1945, they, too, decided to bring their daughters to the conference as their aides.

Photograph of Section Officer Sarah Churchill Oliver, ca. 1943. Reference: Sarah Churchill Papers, SCHL 6/2/21

I was amazed by this discovery. I had studied Yalta numerous times throughout my education, but I had no idea these three daughters had been there. When I looked at the books that had been written about Yalta, I noticed that the daughters occasionally appeared in a very minor capacity to provide a bit of background color, but if their fathers had deliberately selected them to serve as their aides, I believed this indicated their presence there was far more meaningful and that their relationships with their fathers were far more important than we realized. At Yalta, Sarah Churchill, Kathleen Harriman, and Anna Roosevelt not only had a front row view of history. They were also indispensable to their fathers as they laid the plans for peace in the postwar world.

Part of the reason we did not have a full understanding of their remarkable role as “daughter-diplomats” and their rich relationships with their fathers was because the sources necessary to tell their story had not been available. The opening of Sarah’s archive began to change this. Sarah’s sister Mary Soames’ papers are also housed at the Churchill Archive Centre, but at the time I was doing my research, they were not yet open. Mary’s daughter Emma kindly allowed me to have an early look at her papers, which also brought the warm relationship between these two Churchill sisters into view. And through the Churchill family, I was able to connect with the Harriman and Roosevelt families for my research on Kathleen and Anna, which included the opportunity to view their wartime correspondence and interview the women’s family and friends.

Thanks to the Churchill archives, my first book, The Daughters of Yalta: The Churchills, Roosevelts, and Harrimans: A Story of Love and War (William Collins, 1 October, 2020) was born. I am eternally grateful for the assistance and support of Allen Packwood and his colleagues these last three years. This book would not have been possible without you!

A behind the scenes selfie with Allen Packwood.

Catherine Grace Katz is an author and historian from Chicago. She holds degrees in history from Harvard and Cambridge and is currently pursuing her JD at Harvard Law School. The Daughters of Yalta is her first book.