Diaries are another type of life writing we archive here at Churchill Archives Centre. Sometimes people were life-long diarists, giving readers today an intimate view on their day-to-day life. Others however start and stop a diary at different moments in their lives. As some readers might know, some diaries can be detailed, while others are short and perfunctory. Either way, these sources allow us to consider what was important to individuals at the time and why they turned to a diary to immortalise these thoughts.

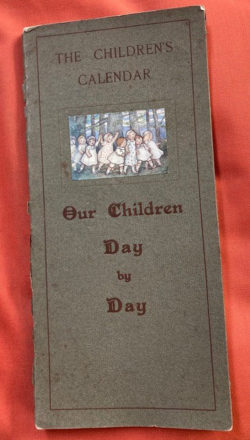

Though many of our life writing collections focus on adults, some of our collections detail the life of prominent individuals in their younger days. Delving into the collections of academic, diplomat and civil servant Sir Roger Stevens (1906-1980), we find a slim volume entitled ‘The Children’s Calendar’.

The volume comprises a page dedicated to each month of the year, next to a jottings and photos page, where parents are invited to record their child’s progress.

The introduction to the volume reads:

“Little facts about our children, if not noted when they occur, may easily slip our memories. The small events in a child’s daily life – from baby’s first tooth or distinct word to big brother’s first cricket match or elder sister’s scholarship – can be noted here for future reference. A series extending over several years will thus form a complete history of the lives of our children.”

Entries include records of when Roger lost his first tooth, his first visit to the Zoological Gardens, as well as when he asked thought-provoking questions, such as in February 1910, “why can’t we see God, why can’t we see him looking out at the sky?”

Readers are treated to a sweet description of Roger’s morning play habits, noting how:

“Roger sleeps well now usually from 7.pm until 6.a.m. When he wakes in the morning amuses himself by reading to his animals or holding a service for their benefit. His family of animals play a very important part just at present and one or more he usually takes everywhere with him. He talks to them and answers for them and they keep him happy and amused.”

Placing this diary in the context of Steven’s prolific journaling later in his life raises questions about generational traditions of life writing – and what we can learn about broader elite life writing practices. The diary was clearly important to Stevens, holding onto it despite regularly moving around in his capacity as British Ambassador to Sweden and Persia.

Source: STVS 8/1/1, Churchill Archives Centre.

Find out more about:

- Stevens’s life writing collections at Churchill Archives Centre, STVS 8.

– Working with diaries by reading:

- Irina Paperno’s What can be done with Diaries?

- Victoria Stewart’s “Writing and reading diaries in mid-twentieth-century Britain.” Literature & History 27, no. 1 (2018): 47-61.

- Joe Moran’s Diarykeeping is an exceptional and heroic act published in The Guardian or watch his lecture for on a similar topic here.

- The winning entries from our Covid-19 diary competition.

Other diaries in our collections:

- Lise Meitner’s pocket diary, 1914, MTNR 2/3 (see just how small it is here).

- Winston Churchill’s desk diary, 1918, WCHL 6/78 (get a glimpse here).

- Mary Agnes Hamilton MP diary collection, 1938-1945, HMTN 1 (and you can read a blog on Mary’s archive here).

- Phyllis Wilmott diary on her work as a medical social worker and life in Hackney, c.1950s, WLMT 1/10.

- Julian Amery MP diary from the time of Suez Crisis, 1956, AMEJ 4/1/9.

- Sir Ian Jacob diaries on his early army career, his work as Assistant Military Secretary to the War Cabinet and as Director General of the BBC, 1917-1982, JACB 1.

If we’ve whetted your appetite, then do get in touch to explore our collections.

Want to catch up with earlier posts in our series? Check out our blogs on autobiographies and biographies and letters.

Looking for useful introductions for working with life writing? Here’s some of our favourites:

- Dobson, Miriam, and Benjamin Ziemann, eds. Reading primary sources: the interpretation of texts from nineteenth and twentieth century history. Routledge, 2020.

- Barber, Sarah, and Corinna Peniston-Bird, eds. History beyond the text: a student’s guide to approaching alternative sources. Routledge, 2013.

- Summerfield, Penny. Histories of the self: Personal narratives and historical practice. Routledge, 2018.

- Saunders, Valerie, “Life Writing”. In Victorian Literature, (accessed 4 Aug. 2021).

By Cherish Watton, Archives Assistant.

Subscribe to Churchill Archives Centre News

Enter your email address:

Subscribe to the Churchill Archives News RSS feed: