The theme for this year’s World Digital Preservation Day is ‘Breaking Down Barriers’, and in this piece I will be discussing Churchill Archives Centre’s approach to that most fundamental barrier in digital archiving; accessing data deposited with us.

Historically, a number of different approaches have been taken to the digital media that we’ve received; at various times we copied data to our servers; we created CDs with copies of the data for use in the terminals in our reading room; we catalogued the material, but didn’t make a copy; and sometimes we didn’t do any of the above when presented with particularly awkward formats.

An 8 inch floppy disk, with 3.5 inch disk for scale. We hold over 200 of these, largely between the Kinnock (KNNK) and Child (CHLD) collections.

Over the last 6 months I’ve been working through all of our digital carriers – CDs, DVDs, floppy disks, ZIP disks, USB drives, and a small number or more esoteric formats such as Digibeta – working out what we can process in-house, re-copying that material to our new standards, and seeking out external contractors where we can’t develop the capabilities to process them ourselves. While I knew there would be problems with things like 5.25 or 8 inch floppy disks, I thought that working with the CDs, DVDs and 3.5 inch floppy disks would be a trivial task, where I could establish a simple process and apply it to all such items, but both presented issues that I – as someone who considers themselves fairly familiar with these things – did not anticipate.

Floppy disks – the problem of different densities

The computers with internal floppy disk drives were been removed from the Archives Centre some time ago now, but I knew that external USB floppy drives were readily available and inexpensive, and that while I expected some intermittent issues – for example, material not formatted for the Windows terminal that I would be using for the copying, or items that had become damaged/degraded over time failing to copy with simple processes – I imagined that I would be able to get through the majority of the c. 300 3.5 inch floppy disks that we hold without much trouble.

I started on a relatively new accession, the papers of Philip Gould, which contained 212 floppy disks. At first, everything went as expected. Of the first 40 disks I processed, 2 only partially copied, and 2 would not copy at all; certainly a good success rate for our initial, simple processes, with those others able to be given more attention later. From here, however, things went downhill fast. Of the next 134 disks in the collection, I could only read 7. A number of these were marked as formatted for Macintosh on their metal sheathe, that was only the case for some items; something else was happening here.

After much web searching, and checking in with the College’s Computing department, I discovered the issue; all these disks I was trying to read were older double density (DD) disks, while those I had started with happened to be the only high density (HD) disks in the collection. I had neither realised that this was a distinction – let alone an important one – or the more pertinent issue that modern USB floppy drives can only read HD disks. For reasons that I don’t fully understand, there don’t seem even to be specialist versions of USB 3.5 inch floppy disk readers that will read DD disks, and while it is still relatively feasible to get hold of older machines with internal floppy drives, this would create requirements for the Computing department to maintain legacy hardware with issues that they had previously sought to do away with via modernisation of our hardware. I remain hopeful that we will be able to implement a solution that allows us to process these 3.5 inch DD disks in-house, but I suspect that we are going to end up with a minimum of 3 workflows – HD/Windows, HD/non-Windows, and DD – for processing what at first I had hoped to be a single, unified group.

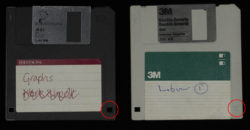

A High Density (HD) disk, left, and a Double Density (DD) disk, right. These examples helpfully list that difference on their metal sheathes, but this is not always the case, and sometimes the only difference is the hole – or lack thereof – in the bottom right, circled for emphasis.

Audio CDs – why some CDs are more similar to DVDs than other types of CD

In a similar vein to the floppy disks, I had thought that we could deal with all typical (12 inch diameter) optical disks – CDs and DVDs – in an identical fashion, at least in terms of getting data from the disks in the first place. Certainly, our methods for providing access to their contents later would need to vary between data disks, audio disks and video, but I did not anticipate issues with the initial step. I was familiar with the concept of disk imaging to create a copy of an entire optical disk – from which you could extract the contents later by ‘mounting’ the disk as if you had inserted it into an appropriate drive in your computer – and had hoped that this would be a simple approach that could be applied to all such items.

Our approach to copying CDs and DVDs has changed in two important ways since that first intention; firstly, disk imaging for optical media in general is no longer our preferred method, because while it is certainly the ‘best’ and most complete copy that can be made, it is very time intensive to do, and generates very large file sizes; a disk image is as large as the total capacity of a disk, and ‘copies’ unused areas, so a 4.7 GB capacity DVD with 200 MB of photos on it would create a 4.7GB disk image. Given both the cost and environmental factors that would be involved in storing such data, we’ve decided to just copy the data stored on the disk (a ‘logical copy’) in the majority of cases.

Secondly, following further research, I discovered that audio CDs – those in the Compact Disc Digital Audio (CD-DA) format – simply cannot be processed in the same way as other CDs. As pointed out by a number of useful blogs linked below, an error prevention portion normally present on CDs is absent on CD-DA, allowing instead for greater storage, but meaning that it would be nearly impossible to get a fully accurate disk image of such at disk. Additionally, you cannot make simple (logical) copies from anything in CD-DA format, and instead have to rely on programs such as iTunes to ‘rip’ the audio instead. As per the advice from other Archives, we aim to use a program that rips with multiple checks, but this does necessitate a totally different workflow for CD-DA than with all other CDs. Indeed, we are happy that our logical copy workflow works well for the majority of both CDs and DVDs, including both data and DVD video, but the different workflow needed for CD-DA underlines again how things which might at the first glance seem alike actually have important underlying differences.

– Chris Knowles (Digital Archivist)

In writing this piece, I’ve hoped to shed some light on the unexpected problems that archives can experience when attempting digital work that might be assumed to be simple at first glance, but also to contribute towards the body of resources that includes the other blogs that I link to below. The problems these blogs discuss are still very much relevant in 2021; indeed, they may cause surprise more often as time passes and we move further from when these formats were widely used in everyday life.

Yale: To Image or Copy -The Compact Disc Digital Audio Dilemma

AVP: An Introduction to Optical Media Preservation

New York Public Library: Preservation Documentation Portal

University of Kent: Adventures in audiovisual digitisation* (part 3)