By Bill Whiteside, researcher at the Archives Centre in 2012, written on 2 July 2020.

I’m writing to share a story about Admiral James Somerville and a cable that he received from Winston Churchill shortly before midnight exactly 80 years ago today – on July 2, 1940. Let me start this long note for a long U.S. holiday weekend with a bit of background.

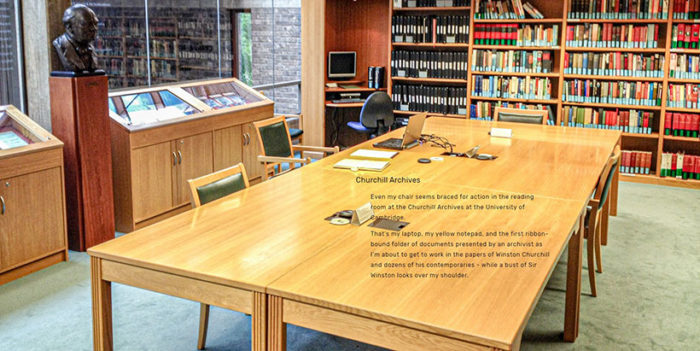

I left my hotel on a June morning several years ago and walked across the centuries-old campus of the University of Cambridge. Twenty-five minutes after starting out, I arrived at the entrance to the Churchill Archives Centre a few minutes before their 9:00 opening time.

I would spend the next 3 days working in the Churchill Archives, where you will find the papers of roughly 600 political and military figures of historical significance; none more significant, of course, than Sir Winston Churchill.

Thanks to the Centre’s helpful website and a delightful exchange of emails with an archive assistant in the weeks prior to my visit, I was ready to dive into my research after just a few minutes of perfunctory introductions and instructions.

That morning was the single most significant, exciting, and intimidating slice of time in the research phase of my project. Just as I sat down, just as I was about to open my first folder of historical documents, I practically said out loud: “I really need to capture this moment.”

I slid my chair back, walked to the end of my reading table, and snapped a picture that shows my laptop, my yellow notepad, and a ribbon-bound folder from the archives. A bust of Sir Winston sits off to the left, as if waiting to peer over my right shoulder as I worked.

Back then, a website for my far-off book was the furthest thing from my mind … but that captured moment is now one of the most visited pages on my site.

Even my chair seems braced for action in the reading room at the Churchill Archives at the University of Cambridge. That’s my laptop, my yellow notepad, and the first ribbon-bound folder of documents presented by an archivist as I’m about to get to work on the papers of Winston Churchill and dozens of his contemporaries – while a bust of Sir Winston looks over my shoulder.

I did my homework before flying to London and taking the train from there to Cambridge. I was familiar with the archives’ rules for researchers. Note-taking is permitted, but only on yellow paper. Pens are strictly forbidden, pencils are OK. Laptop computers? Sure. Best of all, smart phones and cameras are encouraged. A researcher can take pictures of an unlimited number of archive materials in exchange for a daily £1 courtesy fee. I ended up taking more than 700 pictures.

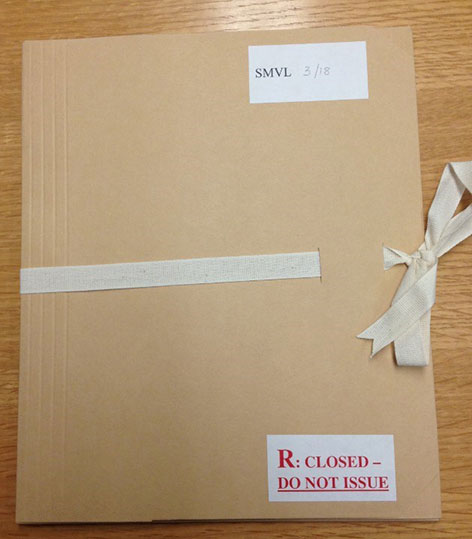

Before traveling to Cambridge, I forwarded a list of the collections that I wished to explore. In addition to the papers of Winston Churchill, I planned to dig through the letters, telegrams, diaries and other papers of several admirals and generals, as well as the hand-written diary of Churchill’s private secretary. Shortly after plugging in my laptop that first morning, I handed an archives assistant a small slip of paper on which I had written the code for the first folder that I wished to review – SMVL 3. After a couple of minutes back in the labyrinth of the archives, she returned and presented me with a large manila folder that was neatly tied shut with a thick beige ribbon – one of the charming touches of the Churchill Archives.

I was surprised when the assistant later instructed me not to re-tie the ribbon when I finished with that folder and was ready to move on to the next set of materials on my list. As I noticed when I handed the folder back, the archivist took a discreet look through the letters and telegrams to ensure that none of these unique documents were mangled or had accidentally slipped between the pages of my yellow notepad.

With this first folder of primary source materials in hand, as I sat back down at my table I felt a wave of excitement and trepidation. This project was now more serious than at any previous point. My natural impulse was to … well … take another picture for posterity. This time I zeroed in on the SMVL 3 folder.

SMVL is an abbreviation for Somerville, as in Admiral of the Fleet Sir James Fownes Somerville. When a British battlefleet – “Force H” – shelled the French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir on the coast of Algeria on July 3, 1940, it was under the command of Admiral Somerville. He is one of the admirals whose papers were donated to Cambridge. I wanted to start with his stories.

The SMVL 3 folder is unlike most other folders that you will find in the Archives. A sticker on the front cover declares – in bright red – “R: CLOSED – DO NOT ISSUE.” (The letter “R” indicates that this file is restricted).

When I sent her an advance list of the collections that I hoped to study, my contact at Cambridge let me know that all of the collections were available for public review, with the exception of one folder from one of the collections – SMVL 3.

That folder includes private correspondence between Admiral Somerville, his wife and other family members – in other words: potentially the good stuff. Access to those papers could only be granted by explicit permission from the Admiral’s grandson, Commander Christopher Somerville.

My contact was kind enough to forward my request to Commander Somerville. In return he sent me an email in which he very graciously granted me access to his grandfather’s private correspondence. He also asked: “Would you please very kindly send me a copy of the book when it comes out?” As you might imagine, Commander Somerville is at the top of my list once I have copies in hand.

Admiral Somerville’s private letters and diaries reveal fascinating dimensions of a career seaman who had been pushed out of the Royal Navy in 1939 due to an unconfirmed suspicion that he might be tubercular, and then recalled to service in time to help lead the evacuation of British forces from Dunkirk in the last days of May 1940. He would later play a significant role in the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck. My primary interest, of course, was to learn everything I could about his career and his personality, with a very specific focus on his engagement with the French Navy at Mers-el-Kebir. The mother lode of information that I discovered at Cambridge has helped shape and enrich my book in countless ways.

Well before I started to wonder if the Churchill Archives would permit a software salesman to pass through their doors, I was inspired by a story that Winston Churchill tells about Admiral Somerville in his book “Their Finest Hour.”

Somerville had embarked from the British base at Gibraltar late on the afternoon of Tuesday July 2, 1940. The 17 ships in the battlefleet under Admiral Somerville’s command included 10 destroyers, 3 battleships, and an aircraft carrier. Force H was scheduled to arrive unannounced at the mouth of the harbor at Mers-el-Kebir in the early morning hours of July 3 to confront the French ships that sat in unsuspecting calm at their berths. The British hoped to entice the French to either join their side or to sink their own ships to ensure they did not fall into German hands. If the French refused to accept the British terms, Somerville’s orders were to sink his former allies’ ships.

Churchill writes that he cabled this exhortation to Admiral Somerville at 10:55 on the night of July 2, 1940: “You are charged with one of the most disagreeable and difficult tasks that a British Admiral has ever been faced with, but we have complete confidence in you and rely on you to carry it out relentlessly.”

That quote – with Winston Churchill’s compassion, leadership and uncompromising resolve all on display – was a key part of the inspiration that led me to dig more deeply into the story of the clash between the British and French fleets, and, eventually, to quit my job and write a book.

As it turned out, not many things would go according to plan in that harbor on July 3, 1940. But, as my book will tell you in bloody detail, there is no dispute that Admiral Somerville embraced Winston Churchill’s charge and carried out his duties with relentless force.

Bill Whiteside

Lancaster, PA, USA

Subscribe to Churchill Archives Centre News

Subscribe to the Churchill Archives News RSS feed: