Archive By-Fellow’s report, Professor Eva-Maria Thüne

I am grateful to Churchill College, Cambridge, for appointing me as Archival By-Fellow in spring 2022, and for allowing me to pursue my academic interests. I am also extremely grateful to have been awarded a grant by the Jennie Churchill Fund to support my research into German Jewish refugees in the 1930s.

Professor Eva-Maria Thüne

My interest in this subject goes back to the year 2017, when I had the chance to gather narrative interviews with former refugees, mainly Kinder from the Kindertransport, a research project whose aim was to find out whether the interviewees, who had all learned German as their first language, maintaining it or not as the case may be (the results of this were published in the book Gerettet; they are also summarized on the accompanying website, and the interviews themselves can be consulted in the Corpus FEGB). Some of my interviewees had stayed at the home of Sybil and Robert Hutton, and for this reason I wanted to get a more detailed understanding of individual cases, not only on the basis of oral memory but as reflected in the documents of the time.

The bulk of my time as a By-Fellow at Churchill College was spent investigating the Professor Robert Hutton Papers in the Archive, while the remaining days were spent in the University Library’s Special Collections, going through some of the papers of Greta Burkill.

In the Hutton papers one can find mainly two different authors and addressees: Robert Hutton and his wife Sybil Hutton, both equally active and present in their attempts to help various groups of refugees: Robert Hutton in finding a position in the UK for academics in flight from Nazi-Germany and occupied countries; Sybil Hutton’s main concern, by contrast, was children (mainly from the Kindertransport), young people or women in search of a place as a domestic servant. In his recent book, Mike Levy notes concerning Sybil Hutton that she was the daughter of Sir Arthur Schuster, a German émigré with a Jewish background; Robert Hutton was a pupil of Sybil’s father, and possessed the double advantage of having experience in industry and knowing Germany well – he was also fluent in German and had built up a considerable network of colleagues across continental Europe [Mike Levy, 2021, Get the children out. Unsung heroes of the Kindertransport. London: Lemon Soul Ltd].

The Huttons lived at the time in Cambridge, in 1 Chaucer Road, near to the Burkills, another family of the utmost importance in the Cambridge Refugee Committee of the 1930s – in particular Mrs. Greta Burkill. Indeed, Mrs. Burkill and Mrs. Hutton were not only both wives of Cambridge professors, both also had a Jewish and German background, and consequently were very well placed to understand the problems of the refugees, not least because they understood the German language.

For me as a linguist, it has been particularly fascinating to discover in various files of correspondence long and articulated letters written in German either by academics seeking employment or by families recommending their children for a position or by the children themselves. Given these aims, these letters are, not surprisingly, very revealing of the situations that the writers found themselves in: often the tone of the letters tells us a lot, especially where the writers were avoiding being too explicit, because they did not feel it was safe to reveal too much. The Huttons must have understood these implicit messages.

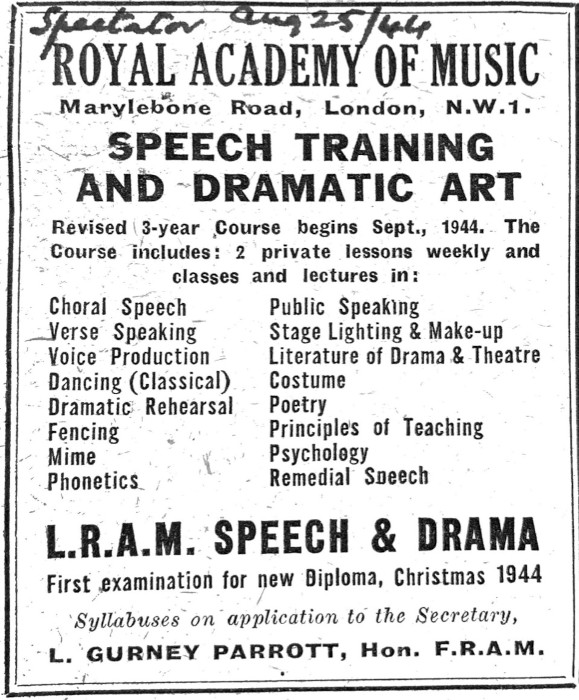

Most of the Kinder of the Kindertransport said that they had learned English very fast, but the Huttons became more and more aware of the difficulties of learning English, especially of the importance of acquiring a native-like accent. In 1944 they tried to find a solution for this problem, asking the Royal Academy of Music about courses in speech training to improve the refugees’ elocution.

HUTT 3/4

Already in 1938 the Hutton household had a German cook, Ilse Königslörger, and had had several young refugee women as domestics, one of whom was Eva Lustig. Eva’s brother Fritz also came over – he had just received his Abitur (equivalent of A-levels) in 1938 and was a talented musician, although at that time he was not able to pursue this interest. Robert Hutton helped him to find a job. When Fritz was interned as an enemy alien in 1940, the Home Office tried to have composer Vaughan Williams write a letter to get him released. But Vaughan Williams was reluctant to do so, querying whether Fritz was a musician of “eminent distinction”, and adding that “one must draw the line somewhere”.

Fritz had told me in the interview that he brought his Cello with him to the internment camp and later, when he joined the Pioneer Corps of the British Forces, he became part of the Pioneer Corps Orchestra. He didn’t mention the letter of Vaughan Williams; maybe he didn’t even know about it.

The By-Fellowship has provided me with the opportunity to reach a deeper understanding of some individual stories of refugees who I had interviewed, as well as opening up new strands to be explored. The whole stay at the College has been a wonderfully stimulating experience. Since there are still some closed files in the Hutton papers regarding other Kinder that might be opened in the coming years, I’m very much looking forward to coming back to the Archive and to the College. Thank you all for everything!

Professor Eva-Maria Thüne