By Russell L. Riley

I arrived in the reading room of the Churchill Archives Centre in April 2022 not with a project, but with a premise.

For the last two decades I have directed the Presidential Oral History Program at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, where my energies have been channelled into recording confidential interviews with former high-ranking White House officials. These sessions are akin to looking at the presidency under a microscope, with our respondents describing in granular detail their daily lives running the executive branch of America’s government.

But having earned a research leave from these responsibilities, I thought it might be useful to consider another approach. That’s where the Churchill Archives Centre came in.

My pandemic reading had included the three volumes of Charles Moore’s authorized biography of Margaret Thatcher—which revealed to me that Lady Thatcher’s personal papers are held at Churchill. And that the principal archivist is one Andrew Riley. (No known relation, although a common ancestor surely roamed the Irish midlands centuries ago.) Andrew almost immediately responded positively to an emailed query about the availability of materials, and from that moment I knew how I wanted to spend my sabbatical. The endorsement of Allen Packwood, director of the Archives, provided official cover for my journey during the Easter Term as an Archives By-Fellow.

The premise? That there are valuable things one might learn about the American presidency by looking from afar. This proposition was richly rewarded.

With the able assistance of the Archives staff, I began my work in the Thatcher papers. The very first documents laid out for me were her travel files to the United States, including a little-known trip as a guest of the State Department in 1967. I was hooked—to the point of distraction.

Given what we know of Thatcher’s later affinity for the United States, and especially her close relationship with Ronald Reagan, the fact of this visit seemed talismanic. Indeed she actually had traveled to California while Reagan was governor there, and made a similar trip to Houston, Texas when it was represented by a first-term congressman named George Bush. ‘There’s a book in this trip!’, I thought—but alas the education of a prime minister would be too big a departure from my normal run of work to make sense.

But it was in paging diligently through other files in the Thatcher collection that I encountered the kind of paper trail I’d been hoping to find.

Occasionally surfacing in the Thatcher documents were confidential despatches from the British embassy in Washington, reporting on emerging developments in the American government. These proved to be right on point: professional assessments of the Washington scene from a unique perspective. Still, with so much already known about Thatcher’s relationship with Reagan himself, the value-added from these specific documents seemed marginal.

Might there, however, be similar despatches, about other presidents, elsewhere in Churchill’s holdings? This is where the big payoff came.

It so happens that the Archives Centre also holds the papers of one Peter Jay—who was Her Majesty’s ambassador to Washington from 1977 to 1979. Jay was not, in his day, considered an especially notable diplomat, in part because was the son-in-law of the prime minister for whom he served—meaning that British users may tend to discount the value of the collection. But Jay, who came from a journalism background, proved to be a remarkable source for me. He was by virtue of his talents and training a highly gifted writer and an acute observer of American politics.

Jay’s confidential despatches from Washington were well crafted accounts of the president of his time: Jimmy Carter. His first such post, from November 1977, still early in the president’s term, was typical: ‘Dr. Johnson’s old friend, Mrs. Carter, “could make a pudding as well as translate Epictetus.” It is increasingly doubted in Washington whether Mr. Carter can.’

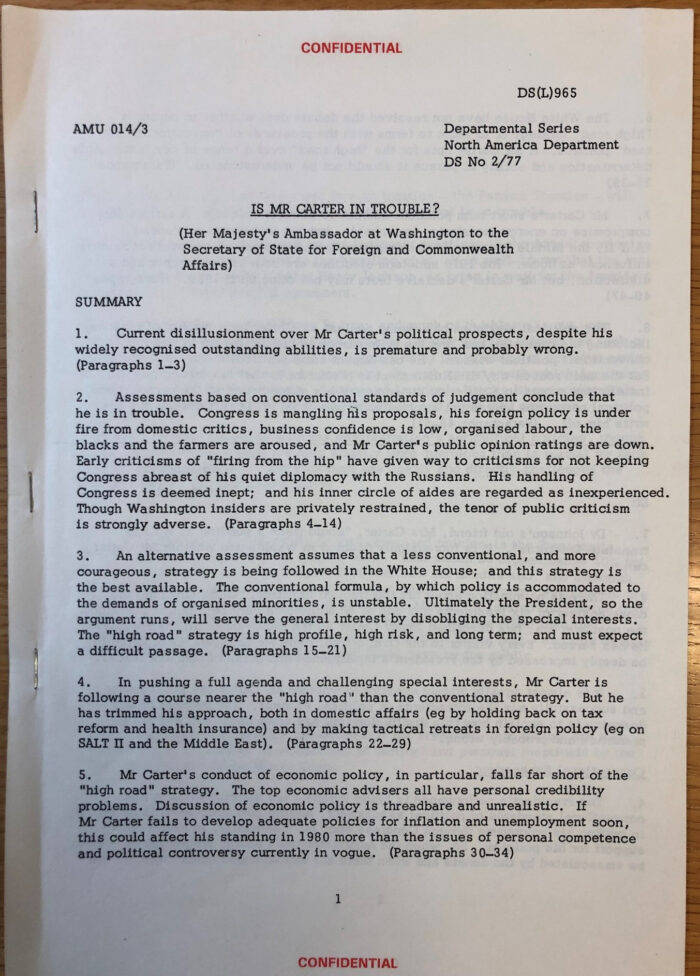

The first page of Peter Jay’s despatch from Washington, November 1977, PJAY 2/33

Jay’s annual reviews, as well as his occasional intervening reports, painted a vivid and insightful portrait of an unusual president serving in unusual times. Jay accurately described for London the perilous cross-currents of American politics as the United States sought to locate a proper role for the institution of the presidency when all the prevailing impulses were to contract executive power after the Vietnam War and Watergate. Carter was caught in the undertow, and the flaws in his own leadership style made him incapable of escaping it.

I’m still today working through the uses to which I may put these remarkable materials. But suffice it to say that anybody who wants a nuanced and dispassionate understanding of the Carter years—both in foreign policy and in the domestic political scene—will profit immensely from these papers. What Jay loses from not having a native familiarity with Washington he more than compensates for by his critical distance and his finely honed observational skills.

Happily, then, my premise was proved right!