Narrowing down our list of collections relating to foreign policy from nearly 90 to 10 is no easy job: the Churchill and Thatcher Papers on their own contain enough material on international relations to keep researchers busy for years. However, this top 10 is an attempt to cover at least some of the key Foreign Office ministers and diplomats who have found themselves in the hot seat during what they might call (in diplomatic language) ‘interesting times’.

Part of a series of subject guides to the Churchill Archives Centre’s collections, these lists are not exhaustive and provide a very subjective window onto some of our personal highlights. Please get in touch with the team if you have any questions about the collections the Archives Centre holds, or if you would like to make an appointment to consult any of these collections in the reading room.

10 BRITISH DIPLOMATIC ORAL HISTORY PROGRAMME

No list of foreign policy collections can begin without the BDOHP. Founded in 1995 by Malcolm McBain, a retired diplomat hoping to capture the memories of his colleagues before they were lost to history, the BDOHP is still recording and transcribing those memories over 20 years later and has reached over 200 interviews –and counting! For an account of British diplomacy from the 1960s onwards, straight from the horse’s mouth, start here.

9 Baron Stewart of Fulham MP (1906-90)

The Labour politician Michael Stewart is the first of our three Foreign Secretaries in the archives, and actually served in the post twice in Harold Wilson’s administration, first from 1965-66, then again from 1968-70, after having to make way, much to his annoyance, for George Brown in the meantime.

The main issues for Stewart to deal with were Vietnam, where he was a solid supporter of the United States (which did not endear him to much of his own party), Rhodesia, Nigeria, where he took the line of supporting the Nigerian government against Biafra during the Nigerian civil war, and the Soviet Union. Vietnam and Biafra in particular made Stewart few friends in Labour, but according to his one-time private secretary, the diplomat Nico Henderson, Stewart was ‘an unsung foreign secretary’ who prevented many possible disasters during his time in office.

Stewart’s Foreign Office papers include files on Vietnam, Nigeria and Rhodesia and visits to the US and Moscow, complemented by his House of Commons papers, two diaries from spring 1968 and early 1969, lectures, articles, photographs and personal correspondence.

Highlights:

-

- STWT 8/1/5-6: Stewart’s diaries for April-May 1968 and January 1969.

8 John Burns Hynd MP (1902-71)

Like his boss, Ernest Bevin, John Hynd was a Trades Unionist and Labour man, who had left school at thirteen to work as a railway clerk, while continuing his education at night school. Between 1925 and 1944 Hynd was a clerk for the National Union of Railwaymen, before becoming MP for the Attercliffe Division of Sheffield in 1944, a seat which he was to hold until his retirement in 1970. He became a minister in Attlee’s government in 1945, shortly after first entering Parliament, serving for two years as Minister for Germany and Austria, as well as Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Later in his political career, Hynd continued his interest in foreign affairs, particularly relating to Germany, as a delegate to the Council of Europe and the Western European Union, and chairman of the Anglo-German Parliamentary Group, also publishing a pictorial biography of Willy Brandt in 1966.

Highlights:

-

- HYND 3: Papers relating to Germany and Austria, 1936-85.

-

- HYND 4: Foreign affairs (other than Germany), 1930-75.

7 Sir Nicholas O’Conor (1843-1908)

The papers of Nicholas O’Conor and his wife Minna are one of our older collections, and give a wonderful picture of diplomatic life at the end of the nineteenth century. O’Conor joined the Diplomatic Service in 1866, and enjoyed a particularly far-flung career, particularly in China, where he served first as Secretary to the Legation and Chargé d’Affaires at Peking in the mid-1880s, then later as envoy extraordinary to the Emperor from 1892-95. From China, he moved on to Russia, reaching the top of the diplomatic tree as Ambassador to Russia, 1895-8 and then to Turkey, 1898-1908.

Highlights:

-

- OCON 4: O’Conor’s letterbooks, containing copies of his correspondence with his colleagues, 1885-1907.

-

- OCON 5-7: diplomatic papers and correspondence, particularly relating to Russia, China and Turkey, 1863-1908.

Postcard from Constantinople, Christmas 1912. O’Conor papers, OCON 16/2/2.

6 1st Viscount Vansittart (1881-1957)

Like Alexander Cadogan five years after him, Robert Vansittart was a diplomatic highflyer from early on, passing top of the list in the 1903 entry examination. Though a fine linguist and confirmed Francophile, his health precluded his taking many posts abroad, and for much of his career he remained in London. He rose to prominence after the First World War as part of the British delegation at Versailles, when he came to the attention of the Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon, serving as Curzon’s private secretary from 1920-24.

Promoted to Assistant Under-Secretary in 1928, Vansittart also became Principal Private Secretary to the Prime Minister, first for Baldwin, then MacDonald. Two years later, while still in his forties, he reached the top of the diplomatic tree as; Permanent Under-Secretary of State, 1930–38. Never a friend to Germany, Vansittart laboured to combat the threat from the Nazi regime, but made few friends in doing so: his commitment to the Hoare–Laval pact at the expense of Abyssinia told against him badly, as did his unpopularity with the new Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden. Despite the prescience of his warnings about Germany, he was moved to the basically empty post of Chief Diplomatic Adviser to the Foreign Secretary in 1938, resigning in 1941. Summing up his career in his posthumously-published autobiography, he declared “Mine is a story of failure, but it throws light on my time which failed too’.

As well as numerous Cabinet and Foreign Office papers from the 1930s, Vansittart’s papers also include some secret official correspondence which did not go through the registry and some semi-official correspondence. Many of his letters relate to his fears about first fascism then communism, while his archive also contains copies of many of his writings, speeches and broadcasts.

Highlights:

-

- VNST II 1: Correspondence.

5 Ernest Bevin MP (1881-1951)

The Trades Unionist Ernest Bevin had been elected (unopposed) as an MP in 1940, and went straight into Churchill’s Coalition Government as Minister for Labour and National Service. After the war, Bevin served as Foreign Secretary in Clement Attlee’s administration, from 1945-51 (the longest stint by any Foreign Secretary since Sir Edward Grey before the First World War). We do not have many of Bevin’s pre-war Trades Union papers (they are held at the University of Warwick), but we do have his political material from 1940 onwards, including his Foreign Office papers, correspondence and speeches. Palestine features here (Bevin had resisted calls for more Jewish immigration into Palestine after the war, having more sympathy for the Palestinian side, before handing the problem over to the UN), as does Britain’s relations with the United States and the Soviet Union in the period between the end of the Second World War and the beginning of another, colder war.

Highlights:

-

- BEVN II 5: Foreign Office speeches, 1945-51.

-

- BEVN II 6: Bevin’s personal correspondence as Foreign Secretary, 1946-51.

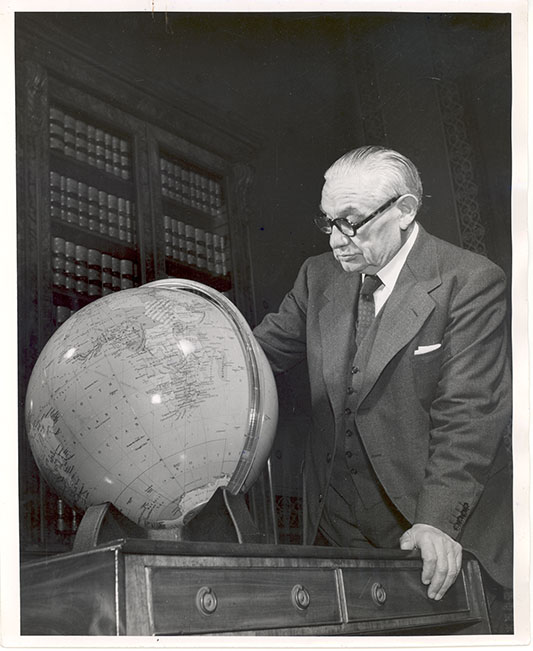

Ernest Bevin, Bevin papers, BEVN II 10/4.

4 1st Baron Strang (1893-1978)

William Strang is another of our elite diplomats, joining the Foreign Office in 1919, where he spent much of his early career dealing with Soviet affairs. He was attached to the secretariat of the Anglo-Soviet conference in 1924, and in 1930 he was appointed acting counsellor in Moscow, where he remained until October 1933. In his last six months in the Soviet Union Strang achieved a notable success in helping the Metropolitan-Vickers engineers caught up in the “Metrovick” trial.

On his return from Moscow, Strang was made head first of the League of Nations section (1933–7) and then of the central department, dealing with German affairs (1937–9). As such he was involved in Chamberlain’s appeasement policy, accompanying him to his meetings with Hitler at Berchtesgaden, Godesberg, and Munich. During the war Strang initially became Assistant Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office (1939–43), then UK Representative on the European Advisory Commission (1943–45). Once the war ended, he became Political Adviser to C-in-C, British Forces of Occupation in Germany, 1945–47, before ending his career as Permanent Under-Secretary, 1949–53 and retiring in 1953.

Besides Strang’s official papers, his collection includes correspondence with numerous historians, particularly on the later stages of his diplomatic career, and nine files of photographs from the different stages of Strang’s life in the Foreign Office.

Highlights:

-

- STRN 2: Foreign Office papers.

-

- STRN 4: Correspondence.

-

- STRN 6/2: Photographs from the Metrovick Trial, Moscow, 1933.

3 Sir Alexander Cadogan (1884-1968)

Marked out as a diplomatic highflyer from the start (he came top in the Foreign Office entrance examinations for 1908), Alec Cadogan has been described as one of the outstanding civil servants of his generation. He was picked out as the best man in the Foreign Office to head the small but important League of Nations section in 1923, but his hopes for the League’s role in achieving disarmament were disappointed, and he accepted the post of first envoy, then Ambassador to China, from 1933-36. He was brought back from China to become Deputy Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, 1936-7, then Permanent Under-Secretary for the unusually long period of eight years, from 1938 right through until 1946. During these war years, he attended Cabinet meetings and some of the high-level Allied conferences, including the Dumbarton Oaks Conference in 1944 and the drafting of the United Nations charter in San Francisco in 1945. He was the natural choice to become Britain’s first Permanent Representative to the United Nations in New York, 1946-50, a post which demanded all of Cadogan’s tact and skill. In a difficult time for Britain, he contrived, in the words of David Dilks, editor of Cadogan’s diaries, “to exercise an influence at the UN out of all proportion to British material strength”.

Highlights:

-

- ACAD 1: Cadogan kept a highly detailed and frank diary for much of his career, from 1933 onwards (no doubt as a way of letting off steam after long days of being the perfect diplomat). An edited 1volume version of the wartime diaries has been published, but there are 39 volumes of Cadogan’s original to explore!

2 Sir Eric Phipps (1875-1945)

If O’Conor is the place to look for relations with the East, then Eric Phipps is the classic diplomat for Western Europe. He joined the service in 1899, as Attaché in Paris, returning to France in 1909, where he was for three years private secretary to the Ambassador, Sir Francis Bertie. After a brief spell as British Secretary to the Paris Peace Congress, and a short home posting at the Foreign Office, Phipps served as Counsellor at Brussels, 1920–22, before he returned to Paris then Vienna as Minister Plenipotentiary. As Europe heated up in the 1930s, Phipps was at the heart of it, a key witness to the build-up to war, first as Ambassador in Berlin, 1933–37, then in Paris, from 1937 until the outbreak of hostilities in 1939.

Highlights:

-

- PHPP I 10: Phipps’s Berlin diaries, 1933-37.

-

- PHPP I 1 and II 1: correspondence with the Foreign Secretary, 1921-39.

-

- PHPP I 2 and II 2: correspondence with Phipps’s Foreign Office colleagues, 1908-39.

A signed photograph of Hitler, from Phipps’s Berlin diaries, 1937. Phipps papers, PHPP I 10a.

1 Baron Selwyn-Lloyd MP (1904-78)

And at number 1, our third and final Foreign Secretary. Initially a Liberal, and a lawyer by training, John Selwyn Lloyd became a Conservative MP in 1945 after serving in the General Staff during the war (and helping to plan the D-Day invasion). He rose swiftly through the political ranks as well, becoming Minister of State in the Foreign Office, 1951-4. After brief spells as Minister of Supply, 1954-5, and Minister of Defence, 1955, he was appointed Foreign Secretary in 1955, and served in this post under first Eden then Macmillan until 1960.

After leaving the Foreign Office, Selwyn Lloyd took over one of the other great offices of State, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1960-2, before ending his ministerial career as Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Commons, 1963-4. In Opposition, he then served as spokesman on Commonwealth affairs, 1964-6, visiting Rhodesia in 1966, and in the following decade was Speaker of the House of Commons, 1971-76.

Highlights:

-

- SELO 5/3-6: Papers from Selwyn Lloyd’s visit to Korea, 1952.

-

- SELO 5: Official and personal correspondence as Foreign Secretary.

-

- SELO 6: Papers on Selwyn Lloyd’s book “Suez 1956: A Personal View”.

-

- SELO 6: Papers from Selwyn Lloyd’s fact-finding mission to Rhodesia, 1966.

— Katharine Thomson, Archivist

Find out more and search the catalogues online:

Subscribe to Churchill Archives Centre News

Enter your email address:

Subscribe to the Churchill Archives News RSS feed: